If there’s anything re-releases and the indie-resurrected 8-bit era have proven, it’s that videogames don’t become obsolete when they’re 15 or 20 years old. Not if they’re excellent. As someone who put his gaming life on hold in undergrad before jumping headlong into the iOS industry on the press side, I drew a huge sigh of relief when I realized this; covering iOS would put me in very familiar territory, I figured. And yet, my touchscreen-powered journey has been alien in some ways. When I put aside the wide price differentials, the importance of content updates, and the simmering War on In-App Purchases, what nags at me is how much App Store success in certain genres has come down to muscling through with production values while gameplay remains pretty basic. Pretty basic, that is, compared to the very best of what I played growing up. Since I use now-fossilized classics as standards for evaluating what floods into the App Store, it’s only fair that I turn my love of digital dissection on these relics and explain what took them beyond the minimums of game design from one avid player’s perspective.

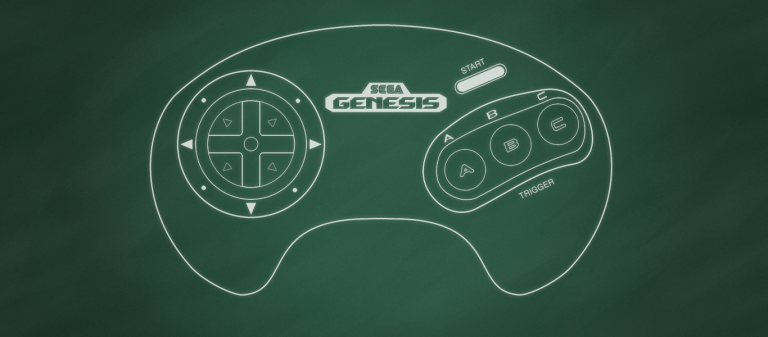

Different genres exist in very different states on iOS of course, so for now I turn my attention to side-scrollers. Action/adventure, shoot ’em up, beat ’em up, platformer, runner — if it scrolls, it rolls into the crosshairs of this opinion piece. Hands down, I spent the most time playing these genres with a SEGA Genesis controller (make that “Mega Drive” for our readers outside the US). It wasn’t for the graphics or music, which had something of a hard edge; aesthetically, the Genesis seemed like whiskey to the SNES’ chocolate milk. It was because SEGA’s console benefited from what must have been some of the greatest minds in the history of game design. A few titles in particular dominated way too much of my childhood: the Sonic the Hedgehog series, Contra: Hard Corps and Streets of Rage 3. Taken together, they illustrate four depth-generating principles that should be well within the iOS developer’s reach.

Lesson One: Story Matters After All

Lesson One: Story Matters After All

I know, I know, some readers will see that as a pretty groan-worthy statement. Lots of devs would probably rather show off their programming chops than their creative writing, and players who want to cut to the chase might point out that Chess has been getting away without a motivating glue beyond its gameplay mechanics for, like, eons. And yet, I can attest that the games and franchises I stuck with over the years were the ones that drew me into strange new worlds. There are only so many ways you can re-invent the jump button, but a game’s world, atmosphere, theme, and message — these are things that can give it a unique flair and keep it in the back of the player’s mind when he or she should really be finishing up some math homework.

The great news is, you can tell a catchy story or build a memorable world without displaying a single line of dialogue or descriptive text. Sonic the Hedgehog numbers one, two, and three mastered the art of minimalistic storytelling. All players really knew was that animals were popping out of every robot this hedgehog bopped with his spiny body, and that the game environments grew ever more mechanical and corrupted the deeper he followed Dr. Robotnik back to his lair. It was a very primal, easily digested theme: animal versus man and machine. The Sonic trilogy’s subject becomes especially ingenious when you consider the time period of its release: the 1990s were dominated by imagery of ducks getting tar pumped from their stomachs, a time when grade schools did their best to drive mortal fear into youngsters who didn’t recycle. A big part of why Sonic stuck with me so long is that its atmosphere and motifs effectively channeled the spirit of the era as I perceived it. So much the better that Sonic’s journey represented a vicarious victory over forces that seemed insurmountable in real life!

Contra: Hard Corps (Probotector for those who called their SEGA Genesis a Mega Drive) fell on the very opposite end of the spectrum. Konami did the unthinkable: they merged the gamebook with the hardest shoot ’em up you could imagine back then. After certain bosses you’d get a choice of where to go next, and the result felt like a choose-your-own-adventure novel where you shot the pages to smithereens. It was glorious. There were four distinct paths through the game, with stages and bosses so unique that the urge to fire that console up again just to see them all was simply magnetic. Granted, Konami wasn’t in the running for any Academy Awards with the game’s bonkers plot. But like Sonic before it, Hard Corps pumped a lot of value out of sheer atmosphere. The most compelling story branches gave you the feeling you were playing through one of H.R. Giger’s nightmares. Bosses even had personality, appearing to throw temper tantrums as the player slipped through their attacks.

Contra: Hard Corps (Probotector for those who called their SEGA Genesis a Mega Drive) fell on the very opposite end of the spectrum. Konami did the unthinkable: they merged the gamebook with the hardest shoot ’em up you could imagine back then. After certain bosses you’d get a choice of where to go next, and the result felt like a choose-your-own-adventure novel where you shot the pages to smithereens. It was glorious. There were four distinct paths through the game, with stages and bosses so unique that the urge to fire that console up again just to see them all was simply magnetic. Granted, Konami wasn’t in the running for any Academy Awards with the game’s bonkers plot. But like Sonic before it, Hard Corps pumped a lot of value out of sheer atmosphere. The most compelling story branches gave you the feeling you were playing through one of H.R. Giger’s nightmares. Bosses even had personality, appearing to throw temper tantrums as the player slipped through their attacks.

If you want to move from subtext to written text without going quite as far as Hard Corps, Streets of Rage 3 is a great example to look at. Its plot contained just one fork toward the end of the game as I recall, but that branch wasn’t a menu choice — it depended entirely on player performance. The sixth stage had you ferreting around a building filled with poison gas searching for an NPC, and the guy would die if you didn’t reach him in time. The game wrapped up with a different final level and end boss depending on the outcome. Since this was back before save points, you felt committed to follow through to the bad ending with the weight of failure on your mind. Nothing like a little pressure! Yes, that is a kangaroo in the linked video by the way, and that brings us to our next lesson.